The Jewish Exilarch’s relationship with the Rabbinical authorities

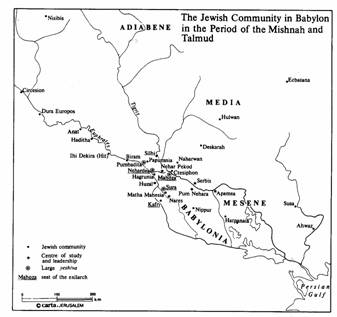

Even before the accession of the Sassanids a powerful impetus toward the study of the Torah arose among the Jews of Babylonia which made that country the very focus of Judaism for more than a thousand years. In 219 CE Rav returned from Israel. It would seem that Palestinian scholarship had exhausted itself with the compilation of the Mishnah; and it was an easy matter to carry the finished work to Babylonia. When Rav returned, there was already an academy at Nehardea under the leadership of an R. Shila, who bore the title Resh Sidra. Upon the death of the latter it was but natural that the much more eminent Abba Arika—whose distinction is indicated by the title of "Rav"—should become head of the school. But, in his modesty, Rav resigned the academy at Nehardea to his younger countryman Samuel, while he himself founded a similar institution in Sura (known also by the name of an adjacent town, Masa Mechasya). Nehardea, a long-established seat of Jewish life in Babylonia, first attained flourishing eminence through this prominent teacher, Mar Samuel; and when, with the death of Rav (247 CE), the splendor of Sura vanished, Nehardea remained for seven years the only academy metivta in Babylonia.

While the Exilarch regarded the entire Judaic nation from the 'Nile to the Euphrates' as his dominion, the Rabbis passed judgment on his subjects – questioning the Jewish descent of most of them. They said "Babylonia is healthy [in Jewish culture and descent]; Mesene [southern Iraq] is dead [intermarried with the Arab bedouins]; Media [northwest Iran and southern Azerbaijan] is sick; and Elam [Kurzistan, the Iranian province on the Persian Gulf] is dying."[1] Although the Exilarch still retained hope of restoring the Judaic nation, he was also aware that his nation was slipping away from him, gradually loosing any loyalty to Judaism or the Land of Israel. Whole communities were converting to Christianity. To counter this, the Exilarch place great emphasis on the Rabbinic academies and Jewish learning.

Although the institution of the Exilarch evolved together with the Rabbinic academies and the Exilarch collected taxes to support the academies financially,[2] the Exilarch formed an independent institution which sometimes competed with or even oppressed the Rabbinical authorities. Under the Sassanids, the community functions of the Exilarch and the spiritual functions of the emerging rabbinic leadership were fairly well defined. He had executive powers and apparently enforced the decisions of the rabbinical court.[3]The first recorded conflict was in the second century CE, between Exilarch Ahijah and the Israeli Rabbinic authorities. About 130 CE, Hananiah, nephew of R. Joshua, migrated to Babylonia before the Bar Kokba revolt, and founded a college in Nehar-Peḳod.[4] Upon the overthrow of the revolt and interruption of communication with Israel, Hananiah set about arranging the calendar, which hitherto had been the exclusive prerogative of the Israeli patriarch. Hananiah even considered the possibility of erecting a Jewish Temple in Nehardea, similar to the ones Onias IV had erected in Heliopolis in Egypt, and in Mecca in Arabia.[5] The former had been closed up by the Romans; the later had fallen into idol worship and superstition. Fearing that Babylon may fall the way of Arabia, the Israeli authorities replied: “If you persist in your intention, seek for yourselves another hill, where Ahijah [the Exilarch] can build you another temple, where Hananiah can play the harp for you [he was a Levite, who were the musicians of the Temple], and confess openly that you have no more share in Israel's God.”[6] This episode made such a strong impression upon the public mind that there are several accounts of it.[7]

The changing of religious requirements especially for the Exilarchs and their households was characteristic of their relation to the religious law.[8] Once when observing the preparations which the Exilarch was making in his gardens for alleviating the strictness of the Sabbath law, Rava exclaimed to his pupils “They are wise to do evil, but to do good they have no knowledge.”[9] The Talmud contrasts the Babylonian Exilarchs, ruling by force, with the Palestinian Patriarchs, Hillel's descendants, teaching in public.[10] Although that quote evidently intends to cast a reflection on the Balylonian Exilarchs, the politics of both offices were looked down upon. The Talmud goes on to explain: “the Messiah can not appear until the Exilarchate at Babylon and the Patriarchate at Jerusalem shall have ceased”.[11]

In spite of the competition for authority, and the Exilarch’s ‘kingly’ status, the Rabbis and the Exilarch functioned together as illustrated by the installation of the Exilarch in his office: “The members of the two academies [Sura and Pumbedita], led by the two heads [the geonim] as well as by the leaders of the community, assemble in the house of an especially prominent man before the Sabbath… The leaders of the community and the wealthy send handsome garments, jewelry, and gold and silver vessels… On Thursday and Friday the exilarch gives great banquets… A costly canopy has been erected over the seat of the exilarch… Then the Torah is read. When the 'Cohen' and 'Levi' have finished reading, the leader in prayer carries the Torah roll to the exilarch, the whole congregation rising; the exilarch takes the roll in his hands and reads from it while standing. The two heads of the schools also rise, and the gaon of Sura recites the targum to the passage read by the Exilarch.”[12] Today, more than a thousand years later, prayers are still said for the Exilarch in the synagogue.[13]

References

- ↑ Kiddushin 71b

- ↑ In regard to Nathan ha-Babli's additional account as to the income and the functions of the Exilarch, it may be noted that he received taxes, amounting altogether to 700 gold denarii a year, chiefly from the provinces Nahrawan, Farsistan, and Holwan. Also, documents discovered at Cairo indicate that Egyptian Caliphs of the Fatimid Dynasty paid a subsidy for the maintenance of the Rabbinical Academy of Jerusalem (Poliakov:II; 61-2)

- ↑ Beer, pp. 57-93. There is no clear evidence that he held the power of capital punishment, but there are references to types of corporal punishment and to extralegal steps taken by his officials to impose their will (see, e.g., Babylonian Talmud, Bava Kama 59a-b, Gitin 67b). The exilarch also regulated aspects of economic life, appointing overseers of the marketplace (agoranomoi) and granting to certain rabbis the exclusive privilege of selling their produce in the market, thus guaranteeing them the advantage over their competition (Beer, pp. 123-26).

The most important function of the Exilarch was the appointment of the judge. Both Rab and Samuel said [Sanhedrin 5a] that the judge who did not wish to be held personally responsible in case of an error of judgment, would have to accept his appointment from the house of the Exilarch. When Rab went from Palestine to Nehardea he was appointed overseer of the market by the Exilarch [Yer. Bava Batra 15b, top]. The Exilarch had jurisdiction in criminal cases also. Aha b. Jacob, a contemporary of Rab [compare Gittin 31b], was commissioned by the Exilarch to take charge of a murder case [Sanhedrin 27a, b]. The story found in Bava Kamma 59a is an interesting example of the police jurisdiction exercised by the followers of the Exilarch in the time of Samuel. From the same time dates a curious dispute regarding the etiquette of precedence among the scholars greeting the Exilarch [Yer. Ta'an. 68a]. The Exilarch had certain privileges regarding real property [Bava Kamma 102b; Bava Batra 36a]. It is a specially noteworthy fact that in certain cases the Exilarch judged according to the Persian law [Bava Kamma 58b]; and it was the Exilarch 'Ukba b. Nehemiah who communicated to the head of the school of Pumbedita, Rabbah ben Nahmai, three Persian statutes which Samuel recognized as binding [Bava Batra 55a].

A synagogal prerogative of the Exilarch was mentioned in Palestine as a curiosity [Yer. Sotah 22a]: The Torah roll was carried to the Exilarch, while every one else had to go to the Torah to read from it. This prerogative is referred to also in the account of the installation of the Exilarch in the Arabic period, and this gives color to the assumption that the ceremonies, as recounted in this document, were based in part on usages taken over from the Persian time. The account of the installation of the Exilarch is supplemented by further details in regard to the exilarchate which are of great historical value; see the following section. - ↑ Compare "Pekod" in Jer. l. 21; called in other places "Nehar-Peḳor," probably after the celebrated Parthian general Pakorus

- ↑ See the Author's essay on "The Prophet Muhammed as a descendant of Onias III"

These two temples were built about the time that Judah the Maccabee rededicated the Temple in Jerusalem. This could explain the Hadith where is says they were built fourty years apart: "Narrated Abu Dhaar: I said, "O Allah's Apostle! Which mosque was built first?" He replied, "Al-Masjid-ul-Haram." I asked, "Which (was built) next?" He replied, "Al-Masjid-ul-Aqs-a (i.e. Jerusalem)." I asked, "What was the period in between them?" He replied, "Forty (years)." He then added, "Wherever the time for the prayer comes upon you, perform the prayer, for all the earth is a place of worshipping for you." Sahih Bukhari, Volume 4, Book 55, Number 636: - ↑ Ber. 63a; Geiger, Urschrift, pp. 154 et seq.; Grהtz, Gesch. d. Juden, iv. 202, 478; Bacher, Ag. Tan. i. 390.L. G.

In the account referring to the attempt of a Palestinian teacher of the Law, Hananiah, nephew of Joshua ben Hananiah, to render the Babylonian Jews independent of the Palestinian authorities, a certain Ahijah is mentioned as the temporal head of the former, probably, therefore, as Exilarch [Ber. 63a, b], while another source substitutes the name Nehunyon for Ahijah [Yer. Sanhedrin 19a]. It is not improbable that this person is identical with the Nahum mentioned in the list [Lazarus 1890, p. 65].

The danger threatening the Palestinian authority was fortunately averted; at about the same time, R. Nathan, a member of the house of exilarchs, came to Palestine, and by virtue of his scholarship was soon classed among the foremost tannaim of the post-Hadrianic time. His Davidic origin suggested to R. Meןr the plan of making the Babylonian scholar nasi (prince) in place of the Hillelite Simon ben Gamaliel. But the conspiracy against the latter failed [Horayot 13b]. R. Nathan was subsequently among the confidants of the patriarchal house, and in intimate relations with Simon ben Gamaliel's son Judah I (also known as Judah haNasi).

R. Meןr's attempt, however, seems to have led Judah I to fear that the Babylonian Exilarch might come to Palestine to claim the office from Hillel's descendant. He discussed the subject with the Babylonian scholar Hiyya, a prominent member of his school [Horayot 11b], saying that he would pay due honor to the Exilarch should the latter come, but that he would not renounce the office of nasi in his favor [Yer. Kilayim 32b]. When the body of the Exilarch Huna, who was the first incumbent of that office explicitly mentioned as such in Talmudic literature, was brought to Palestine during the time of Judah I, Hiyya drew upon himself Judah's deep resentment by announcing the fact to him with the words "Huna is here" (Yerushalmi Kilayim 32b). - ↑ Ber. 63a; Yer. Ned. 40a; Yer. Sanh. 19a

- ↑ Pesahim 76b, Levi ben Sisi; Hullin 59a, Rab; Avodah Zarah 72b, Rabba ben Huna; 'Er. 11b, Nahman versus Sheshet; 'Er. 39b, similarly; Mo'ed Katan 12a, Hanan; Pesahim 40b, Pappai]

- ↑ 'Er. 26a, in the words of Jer. iv. 22

- ↑ Sanhedrin 5a on Genesis 49:10

- ↑ Sanhedrin 38a

- ↑ Seder 'Olam Zu?a, in Neubauer's Mediזval Jewish Chronicles, ii. 68 et seq. Emphasis added.

- ↑ Of the mass deportation of Jews by the Romans in 70 C.E. many were re-settled in Provence, France, then called Narbonensis. Later Pepin (king of France) installed Machir, son of the Exilarch's sister, as the Jewish King of Narbonne. Probably because of the Exilarch’s associated with France, the prayer for the Exilarchs is still mentioned in the Sabbath services of the Ashkenazim ritual. The Aramaic prayer "Yekum Purkan," which was used once in Babylon in pronouncing the blessing upon the leaders there, including the "reshe galuta" (the exilarchs), is still recited in most synagogues. The Jews of the Sephardic ritual have not preserved this tradition.